It’s been a long time since I wrote for this space. When my mom first passed, writing helped. I kept my words measured, each phrase carefully chosen for coherence. I kept a tight hold on sanity and reason by creating a world of carefully controlled sentences and thought. But all the while, behind the keyboard, I was screaming into the void, howling into a black sky where no moon ever rose, whirling lost in the chaos of hurt and raw anguish. Writing to try and find my mother in an emptiness I could not pierce. Eventually, writing my grief exhausted me.

It’s been six years since she passed. Grief has ebbed and flowed through those years. I have learned (sort of) to live without her, but it’s life with an emotional limp, a curvature in the spine of my splintered heart.

This week I was at my parent’s house, the family home. I woke up on Thursday morning with a song running through my head: Kermit the Frog singing Rainbow Connection. I have not heard that song in years, even when in the early months of the pandemic Kermit came out of retirement to gift the world a video of him reprising his biggest hit. I watched it Thursday morning and cried.

The weather has been unseasonably warm in California, and the soil around my parents’ house is already baking and cracking, dry and dusty instead of the usual February muck. “No use to plant a garden, “ my father insists. “They’re going to shut us down for water this year if we don’t get rain.”

In truth, he hasn’t gardened since the day my mother passed. What was once a blowsy, flowerful yard, a garden that stopped people in their tracks to admire and exclaim, is now bare soil with only a few deep-rooted shrubs that linger despite neglect. We have finally, my Dad and I, in the last year, begun to talk a bit about her death, and we’ve both agreed that all our heart for gardening left when she left. I know it shouldn’t be that way, but it is.

In the back yard, where she grew lettuce tomatoes, beans, cucumber, kohlrabi, strawberries, plums, and enough zucchini to frighten the neighbors, only two productive trees remain: a Santa Rosa Plum and a Meyer lemon.

The Meyer lemon produces prodigiously. Branches bow like prayers under clusters of lemons in various states of maturity. Old grandmother lemons, thick wrinkled rinds darkened by sooty mold hang in the interior of the tree, while a bit further out along the thorny branches grow middle-age lemons, ruddy orange and full of sugars. At the ends of the branches young lemons an innocent yellow tinged with green nod under blossoms that scent the branch tips.

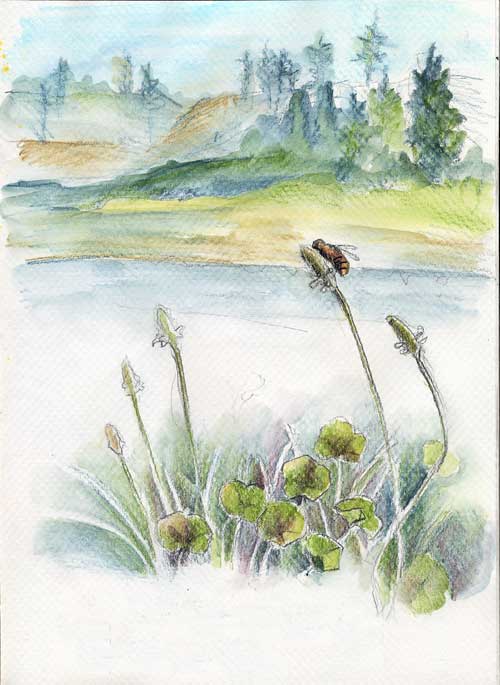

I spent some time picking lemons, smelling the fresh scent, the light lemony essence that mingled with the perfume of a Bay Area spring. Star jasmine, Daphne, early roses, narcissus. In that barren back yard I felt the presence of my mother’s past gardens, the ghosts of bean rows and squash leaves. The wraiths of past tomato plants haunted by the buzzing of long-gone bees.

Can involuntary memory—startled into existence by a scent, a taste, a sound, just a few notes in a pentatonic scale—eclipse time, fold time as if the years are accordion pleats, gussets that close onto themselves and play two time-tunes so close that past and present nearly touch? Do we carry time in our noggins, the hours, days, and years resting along our corrugated brains? When those folds are squeezed like a bellows by scent, sound, taste, even sight, does the reality of the past leap like electrons across space and open in our presence like flowers scenting the air?

The mélange of smell followed me into the house, where it wound its way through the scents of laundry detergent, last night’s dinner, and the faint but still present smell of my mother. My dad watched a Western on the tv. In the distance the commuter train blew its horn, and a dog barked. Time slipped. For the first time in six years, I felt my mom’s presence at the house, as if she had entered with me, peeling off her gardening gloves and saying, “well, we had better get your father fed.”

I heard in my head Kermit singing, “All of us under its spell. We know that it’s probably magic…”

On that warm spring day I imagined the bellows of time closing for a brief moment as memory ran through time’s wet-tuned reeds. Past and preset merged. In the tree at the door a chickadee sang through the leaves, “hey sweetie, hey sweetie, hey sweetie,” and I got my dad some dinner.